SEXUAL MINORITIES UGANDA

(SMUG)

SAFETY AND SECURITY OF THE LGBTIQ+ COMMUNITY IN UGANDA

A PRE-COVID 19 TO POST-COVID 19 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS

A publication of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG)

Kampala, Uganda

December 2020

Researchers

GEOFFREY OGWARO

Senior Research and Policy Officer-SMUG

&

REGINA TUSIIME

Research Assistant/Research and Policy Officer-SMUG

SEXUAL MINORITIES UGANDA(SMUG)

Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) is a non-profit, non-governmental network organisation formed in 2004 to address the need to protect and support lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer plus (LGBTIQ+) persons in Uganda. SMUG advocates for legal and policy reform while simultaneously monitoring the human rights situation for LGBTIQ+ persons in Uganda. AS a network organisation, SMUG coordinates the efforts of 18 LGBTIQ+ organisations in Uganda who’s combined mission is to bring strive towards equality and non-discrimination for LGBTIQ+ persons from all walks of life. These organisations provide a plethora of services to the LGBTIQ+ community including access to health, counselling, guidance, as well as support for the economic empowerment of LGBTIQ+ individuals. SMUG works closely with local, regional and international human rights organisations and human rights activists with one goal: to end discrimination and injustice towards LGBTIQ+ persons in Uganda and ensure that all Ugandans are equally respected and valued no matter their sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression or sex characteristics (SOGIESC).

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

For the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer plus (LGBTIQ+) community in Uganda, safety and security have always been and continue to be one of the biggest concerns. This is because equality and non-discrimination are still not fully enjoyed by them. The social, political, economic and legal environment often works against them rather than for them. This situation often translates into several human rights violations, including violence, against the LGBTIQ+ community of individuals. This rapid situational analysis is one of the quick steps among many others that have been done and published before, to once again document through research, the situation as it pertains to the safety and security of this group of persons in order to use the data to secure to the extent possible, their freedom from violence or threats of violence, and discrimination.

This report looks at the safety and security situation of the LGBTIQ+ community in Uganda between 2019 and 2020, and nuancedly includes the period in 2020 when the novel COVID-19 disease started spreading across the globe (and eventually in Uganda), leading to stringent controls in the form of Presidential Health Guidelines to prevent its spread in the country. These guidelines were both positively and negatively perceived and implemented as is seen in the report. The therefore led to human rights violations against LGBTIQ persons because they were not thoroughly thought through as well as being made open to abuse by local authorities and the state security machinery.

The report examines the specific safety and security risks and incidences during the period in question, the source of these insecurities, the perpetrators of the violations, the remedy-seeking behaviour of victims and finally delivers a set of non-exhaustive recommendations.

The survey and focal group discussions that led to this report point us to some key findings that need to be continuously considered going forward on any social change, safety and security, legal or service projects and programmes developed for the benefit of the community of LGBTIQ+ individuals in Uganda: The research found that the social environment is the biggest factor bringing about the lack of safety and security for LGBTIQ+ persons. By the social environment, the research meant family and home of LGBTIQ+ persons, persons in the vicinity of the home of LGBTIQ+ persons, and friends or acquaintances as well as the mobile communities through which LGBTIQ+ persons travel or commute, including the transport community (public transport). The other factors after the social environment and in order of most impacting and least impacting on the safety and security of LGBTIQ+ persons include the legal framework in the country that still criminalises LGBTIQ+ sexual conduct and constitutionally disallows same-sex marriage, the economic environment, and the political environment. With the political environment for example, the research looks at the impact of public utterances by political leaders especially during electioneering period. The example is given of the President’s accusation of foreign powers and homosexuals supporting the opposition during the current election campaigns of 2020, a situation that could lead to vitriol against and insecurity for the LGBTIQ+ community and their activists and organisations.

The research also reveals some of the actual incidences of insecurity and lack of safety for the LGBTIQ+ community and among them were verbal vitriol, police harassment and arbitrary arrests and detentions, organisational office raids and destruction of property based on sexual orientation and sexual orientation. However, the research also reveals that the LGBTIQ+ community can also be a serious threat to itself. Some of the key issues that came up in the data collection stage were Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and blackmail by either pretend LGBTIQ+ persons or real ones.

The period of COVID-19 also brought in some unique safety and security challenges for the LGBTIQ+ community. Key was the misinterpretation of the Presidential Guidelines by-law on the prevention of COVID-19. The Presidential Guidelines were unclear especially on what entailed a big gathering when it came to restricting public gatherings and therefore did not clarify the place of organisations that had beneficiaries housed in shelters such as the LGBTIQ+. The same guidelines did not specify how many people were allowed to reside or congregate in a home and yet, in the case of one LGBTIQ+ shelter, they were implemented in a way as to warrant the arbitrary arrest and detention of 20 LGBTIQ+ persons from the shelter administered by Children of the Sun Foundation (COSF).

The above are few of the issues that this report looked at. Finally, the report gives suggested solutions to mitigate some of the safety and security concerns raised, and among these are: further building the capacity of the LGBTIQ+ community and its activists on safety and security strategies; continue to equip the police and local council leaders on LGBTIQ+ issues so that they are aware of their Constitutional limits regarding the arbitrary arrests and detentions that they are prone to; continue to incrementally target bad laws through advocacy and dialogue with legal entities like the Uganda Law Reform Commission and the legislature to lead to decriminalisation of same-sex sexual conduct because these laws inform the homophobia that is within the society and within public institutions and; strive to change social perceptions of LGBTIQ+ persons through education that tackles myths, negative attitudes and discourages violence against other human beings based on their differences.

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

For the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer plus (LGBTIQ+) community in Uganda, safety and security has over the years been and continues to be one of the biggest concerns. This arises from different contributing factors that are legal, political, economic and social. Over the years, LGBTIQ+- led organisations have worked tirelessly to improve the safety and security situation for LGBTIQ+ community members, their organisations, and their activists. In the period before this situational analysis, there were programmes that have, through the various LGBTIQ+ organisations and with support from different donors and development partners, equipped the LGBTIQ+ community of activists and individuals with knowledge and skills on safety and security. An example is a security and safety empowerment programme that was run by Mbarara Rise Foundation (MRF), a rural LGBTIQ+ organisation based in Western Uganda in 2018 with support from GlobalGiving.[1] This programme covered several pertinent areas for the participants such as digital security, understanding the rural working environment, analysing security incidents and threats, risk assessment for sustainable strategies, and tactics and individual safety management approaches.[2] Nonetheless, the security situation of the community is one that still needs to be improved further because it usually oscillates between bad and improved. Till today, LGBTIQ+ Ugandans and residents still wake up to risks, threats and incidents such as police harassment, arbitrary arrest, and abuse by the police and other state security agents[3].

The year 2020, has however posed new challenges as well as escalated the already existing risks and threats especially after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March.[4] Several measures were put in place by the state to contain the spread of the virus. Some of these measures included restricting movement or banning it completely; closing businesses and work places except for what was deemed as essential services such as food markets, food stores, health facilities and pharmacies. For the LGBTIQ+ community however, some of these measures have been more constraining than they have been enabling and this has led to security and safety risks and incidents in the LGBTIQ+ community.The measures have also led to the abuse of the guidelines on the prevention of COVID-19 with persons being arrested on the pretext of COVID-19 prevention when in actuality the source of the arrest is that they were suspected of being LGBTIQ+ persons.[5] According to a survey that was done by Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) in June 2020, 50% of the respondents said they had experienced violence from local security operatives and the police; 54.55% acknowledged violence from family members while 63.64% said that their biggest concern was the threat of violence towards LGBTIQ+ people from all sources.[6]

This report is a rapid security analysis of the safety and security of the LGBTIQ+ community members just before the pandemic (2019), and during the pandemic (2020). It, on a rapid and skimming scale, highlights what has stood out in terms of safety and security threats and incidents and how the pandemic has contributed to escalating the already existing lack of safety and insecurity for members of the community.

STATEMENT AND ANALYSIS OF THE PROBLEM

Security threats and incidents against the LGBTIQ+ community started being brought to light and to be informally documented when the community became political and socially cohesive, and started informally organising around LGBTIQ+ rights in the late 1990s. This led up to the establishment of some of the first LGBTIQ+ organisations such as Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG) and Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) in the early 2000s to advocate for the human rights of LGBTIQ+ persons.[7]

These organisations became more aware of these security threats and incidents against the LGBTIQ+ community because the victims could now find individuals and institutions to reach out to for support. Since then, there has been more and more visibility of LGBTIQ+ organisations and activists because of their advocacy, and with that, a proportionately bigger safety concern for the LGBTIQ+ community in the country. This is partly due to the confidence it has generated in many LGBTIQ+ individuals who have then either come out to their families and friends, or now live more active LGBTIQ+ lives. The downturn however is that it has made them more susceptible to be exposed to dangers or discriminatory acts within the immediate homophobic society.

As part of the above factor, Ugandan LGBTIQ+ persons are susceptible to a greater measure of security incidents and threats because of the unfriendly local legal, political, economic and social environment. The environment is made of criminalising laws as well as a general population that has become more and more openly homophobic partly due to the negative populist rhetoric displayed by political and religious leaders especially in the wake of the Ugandan parliament having attempted to introduce an extended criminalisation of same-sex acts and queer sexual and gender identities in the form of the Anti-homosexuality Act (AHA) of 2014[8]. Although the Anti-Homosexuality Act was later repealed on grounds of technicality (not following rules of Parliamentary procedure), it succeeded in creating a further mass of people who are homophobic or violently hostile towards LGBTIQ+ persons. The AHA contributed to negative attention towards the LGBTIQ+ community as well as the extension of myths about who they are and what they do. Myths and misnomers such as LGBTIQ+ people recruit children into homosexuality, they are recruited by the west, and that being gay is unnatural were perpetuated during this period of agitating for the AHA to be passed into law.[9]

The COVID-19 pandemic has also contributed negatively to the security situation for LGBTIQ+ persons as a result of the Presidential Guidelines for protecting against the virus.[10] These guidelines included disallowing the non-congregation of initially an unspecified number of people and particularly affected LGBTIQ+ shelters, exposing them to raids, arrests and closures. LGBTIQ+ shelters were established by some organisations to cater to the problem of homelessness for LGBTIQ+ youth and adults who found themselves unable to provide for themselves due to either being fired from work for being LGBTIQ+ or disowned by their families for the same reason. The problem with the Presidential Guidelines was that they were issued in a generic manner via speech by the president and did not consider unique cases such as people gathered together by necessity. For example the guidelines forbade a list of gatherings: educational institutions, religious gatherings, political and cultural gatherings, work places, weddings, funerals, public transport, and night clubs or music shows.[11] They did not consider homeless shelters such as orphanages, women’s shelters let alone LGBTIQ+ shelters, not that they would have even been contemplated. The guidelines assumed the position of everybody staying home in their more or less small nuclear families to stem the spread of the pandemic. This anomaly led to the raiding of the LGBTIQ+ shelter Children of the Sun (COSF) in the early weeks of the pandemic.[12] Also, it gave lee way for communities to use COVID-19 as a pretext to execute their homophobic actions.

Therefore, having analysed the problem, the number of safety and security incidents and threats have risen and fallen depending on the trigger situation at hand. These have ranged from people informing state security agents when they see LGBTIQ+ persons gathered as was the case with the COSF LGBTIQ+ shelter, to landlords evicting their LGBTIQ+ tenants on realising that they are LGBTIQ+, a result of their legal, social, cultural and religious biases towards homosexuality. The above factors have therefore contributed immensely towards the violation of the rights of the LGBTIQ+ community in Uganda.

This situational analysis is intended to have a look at the safety and security situation for the community starting from 2019 and getting into 2020, but also to look at the near future in terms of safety and security. Additionally, there are measures that have been used to mitigate or redress breaches to security and safety for the LGBTIQ+ community, activists and organizations. These are also noted in this situational analysis.[13]

SCOPE

This study investigated and analysed the safety and security situation of the LGBTIQ+ community in Uganda. Although the study found a concentration of safety and security incidents in the central region that is made up of Kampala, Wakiso and Mukono areas/districts, there were incidents that surfaced in other parts of the country as well. The concentration that emerged from incidents in the central region could be attributed to the fact that these are more concentrated urban and peri-urban settings with a more liberal and cosmopolitan setting for LGBTIQ+ persons due to the fact that many seem to have publicly come out . This is opposed to more rural-based towns and villages where people do not tend to openly express their sexuality or gender identity because of the more conservative cultural settings they find themselves in.

The study also looked at the incidences of security and threats among the LGBTIQ+ community and the manner in which the state responded to reported incidences or threats.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- What are the situational factors that manifest themselves into physical and mental insecurities for LGBT communities in Uganda?

- What insecurities are LGBTIQ+ persons encountering and where do these threats and incidences emanate from/who are the perpetrators?

- How has the advent of the COVID 19 pandemic affected the security of the LGBT community?

- What are some of the measures that the LGBTIQ+ community members and organisations have used to mitigate and address safety and security concerns and what has been the results of these measures?

- What solutions are proposed that will enable the LGBTIQ+ community to be safer?

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Methods used

This situational analysis used qualitative and quantitative methods. For the quantitative data, a survey questionnaire with closed-ended multiple choice questions was developed and disseminated to respondents online. Out of over 20 emails that were sent out with the link to the survey, 14 respondents filled in the survey. Data was then generated from the questionnaires and analysed. For the qualitative data, one online focus group was assembled and interviewed using open-ended and probing questions that generated more analytical narratives and stories. The focus group was made up of one general group of 28 participants that consisted of ordinary LGBTIQ+ individuals as well as activists. Due to time constraints, the group was not split up into smaller ones but the researchers made sure enough time was allocated to the exercise to solicit in-depth responses from the participants. Individual oral interviews were not planned for because of time constraints (and the difficulty of people devoting time for individual interviews even via phone call) but also the need to have online interactions for the avoidance of COVID-19. It was made sure that all the letters in the spectrum LGBTIQ+ were represented. However, there were no intersex persons represented because they did not respond to the call. This is a noted shortcoming of the research as the voices of intersex persons were not represented. However, it can also be argued that intersex persons have their own unique challenges in general and therefore a tailored assessment might be required for them that may generate a more nuanced outcome.

Desk research was also done specially to analyse already written stories, news publications and laws and regulations that had meaning for the analysis.

Sampling

The study collected data from ordinary LGBTIQ+ individuals as well as activists in the LGBTIQ+ movement in Uganda. The sample consisted of 28 persons from various sexual orientation and gender identity backgrounds, and 20 who were also subjected to an online survey tool, of which 14 responded. The sample was purposively selected to be representative of lesbian women, gay men, bisexual men, bisexual women and transgender men and women.

CHAPTER TWO

RESEARCH FINDINGS

METHODOLOGY

Representativeness of the population

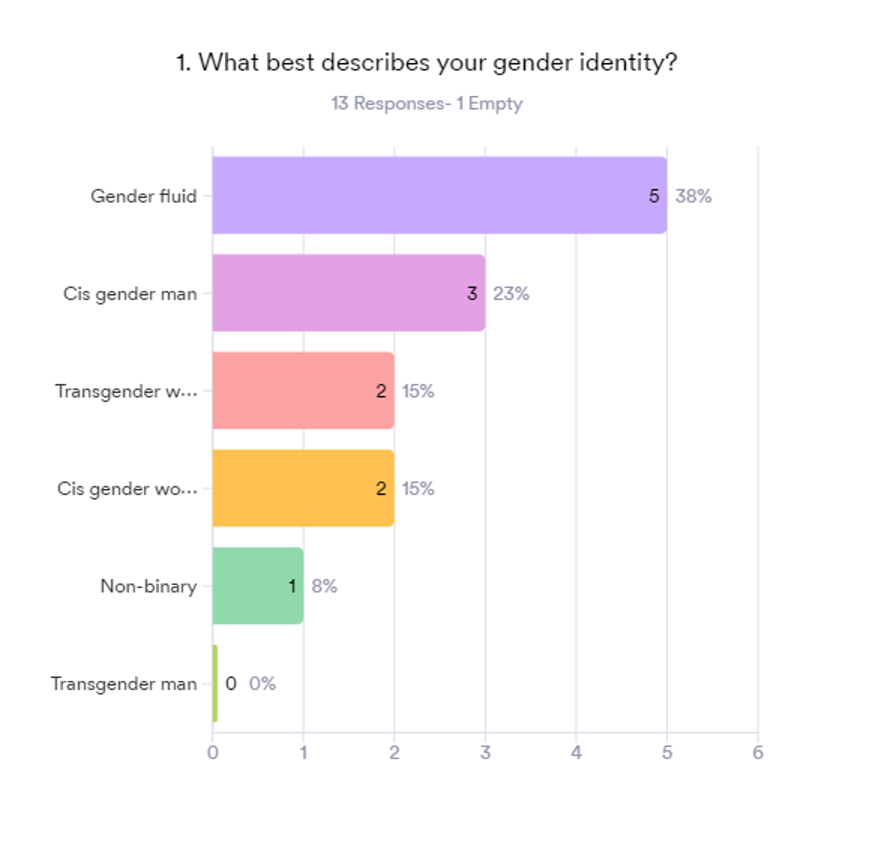

Gender and gender identity

The data collected was fairly representative of important gender population blocks: Those who identified as women represented 30% of the respondents (represented by both transgender women and cis-gender women among the respondents) and 23% reported identifying as cisgender men (none identified as transgender men). Those who identified as non-binary or gender-fluid were 46%, giving the possibility of still a higher representativeness of all the genders and non-genders with 38% identifying as gender-fluid. *Gender fluidity here refers to persons who will identify with any of the binary genders at a given point in time while non-binary refers to persons who do not identify themselves according to any of the gender binary identities.[14]

Graph 1.

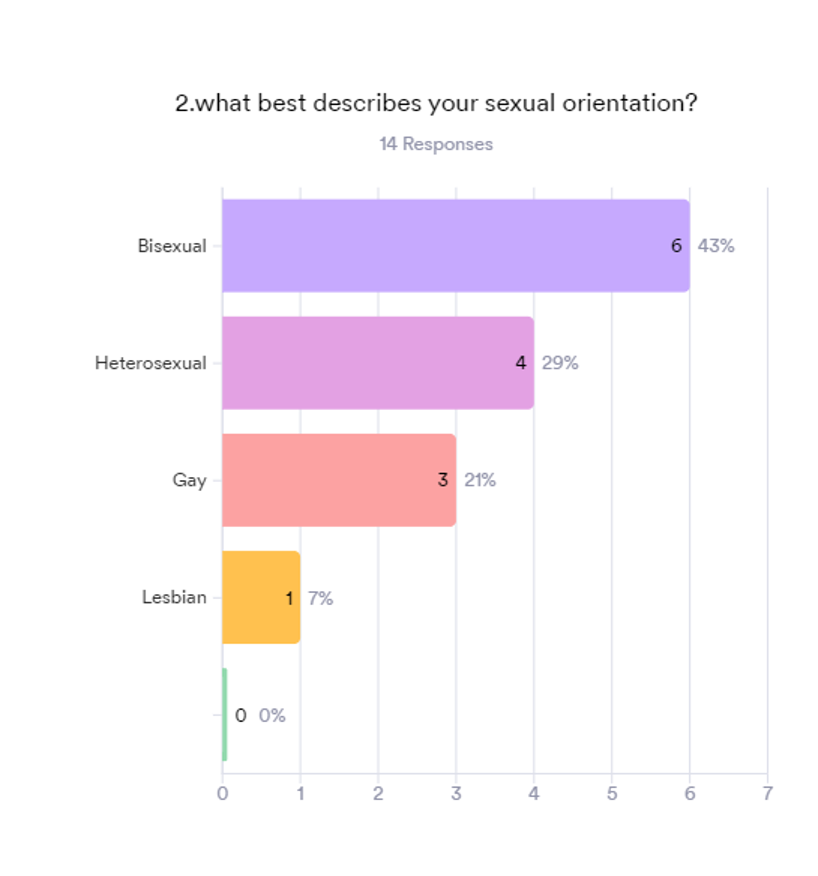

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation was also fairly represented with 43% identifying as bisexual, 21% identifying as gay and, 7% identifying as lesbian. The percentage of respondents identified as heterosexual was 29% – a figure that refers to transgender respondents who identify as heterosexual sexual-orientation-wise.

Graph 2

ANALYSIS OF THE SECURITY SITUATION

The analysis includes an assessment of the COVID 19 pandemic conditions and the associated restrictions on gatherings, movements, work, travel and others that are the source of insecurity for the LGBTIQ+ community or what could be termed as the general roots of insecurity at any given time in the country. The analysis also includes an assessment of the real security incidents experienced from 2019 going into 2020.

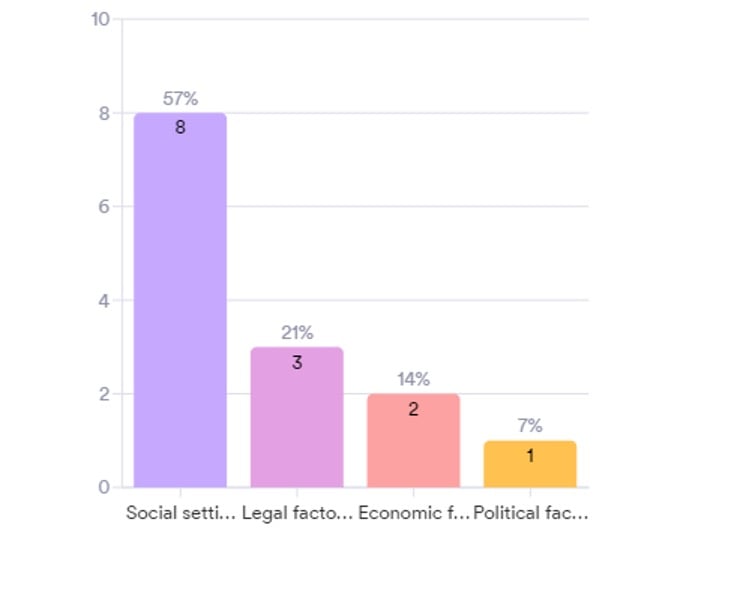

Roots of insecurity for the LGBTIQ+ community in Uganda

Graph 3

*Legal factors include Constitution of Uganda, statutes and policies.

*Economic factors include workplace, employers, work colleagues.

*Political factors include local and political leaders.

The survey inquired about some of the environmental or situational factors that would, could or might lead to safety and insecurity issues for the community in the country. The social setting came out as the biggest insecurity source, with 57% of the respondents pointing it out. The social setting is defined as the family or home environment, neighbours and friends/acquaintances. This is supported by stories around community dwellers calling the police to report organizations like Ice Breakers Uganda (IBU), an LGBTIQ+ organisation based in Kampala:

“The community near IBU is a threat. Last year they called the LC [Local Council] and said IBU has beds and condoms for sex. The LCs inspected. So IBU discussed with the LCs. We have to talk to LCs before [before we introduce an activity or organization in an area]. They used to harass our Trans (beneficiaries), now they call us to inform us about the arrest of Trans people [in the community around IBU].”

BL, Executive Director – IBU – Kampala.

Another respondent raised the issue of the police being trained on the issues they work on and are aware but the neighbouring communities to their offices remained hostile:

“Our landlady introduced us to the LCs and we work with him [the Local Council leader]. But the neighbours are the problem. Because of the threats from the neighbours, we decided to register the organization for legitimacy so that we could confidently introduce ourselves to the local leaders.”

BW – Executive Director – Holistic Organization to Promote Equality – Hope Mbale – Mbale, Eastern Uganda.

Legal factors such as the legal framework and LGBTIQ+ unfriendly policies came out as the second biggest contributor to the community’s lack of safety and insecurity. This refers to the fact that Uganda still criminalizes same-sex sexual acts,[15] and prohibits same-sex marriage in the Constitution.[16] The relationship between this factor and insecurity is that it is the single other factors apart from culture and religion, which informs the negative social attitudes towards homosexuality and gender non-conformity. Therefore, it is a factor that leads to the first one mentioned previously, that of the social attitudes embedded within family life, neighbours, friends, and society in general.

Economic factors such as the environment at work and the attitudes of employers and colleagues at work were rated the third factor with 14%, which causes insecurity and lack of safety for the community. The reference made here is the possibility of harassment, suspension and firing from a job for being gay, bisexual or gender non-conforming, especially when that information comes out to the employer. Although no direct anecdotal information was given by any respondent alluding to this, it is a figure that shows the relatively high possibility of threats being made on LGBTIQ+ persons at work or even actually carried out, including firing, verbal attacks, physical attacks and arrests by police.

The last environmental factor alluded to that contributes to the community’s safety and insecurity issues is political factors. This refers to the lack of political will from political leaders to defend the LGBTIQ+ community from violations but instead, attack them through vitriolic rhetoric for what are be populist reasons. This factor was particularly alluded to in the focus group discussions. One respondent said:

“The greatest threat right now is politics and [election] campaigning. I expressed interest in running for office but there were lots of SOGIE related threats by opponents. For example, Dr Stella Nyanzi [a contestant for a Parliament seat in the 2021 elections and an ally of the LGBTIQ+ community] and Bobi Wine [a presidential aspirant and reformed moderate sympathiser of the LGBTIQ+ community] are always bashed on SOGIE issues.”

IRM – Communications Manager – Spectrum Uganda Initiatives – Kampala, Uganda.

Actual incidents and threats of insecurity before and during the COVID 19 pandemic

The LGBTIQ+ respondents were asked what actual insecurity incidents happened to them in the period 2019 to the writing this report. This period included the time before the COVID 19 pandemic prevention measures were officially announced. . The following are the findings:

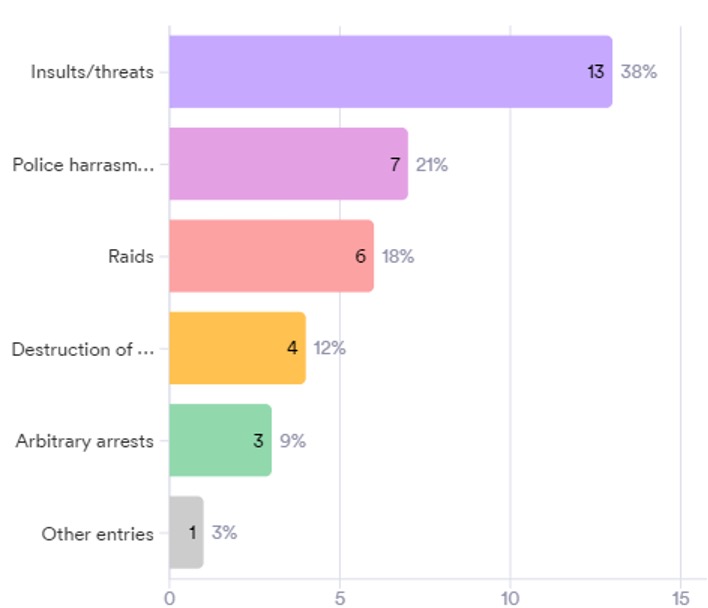

Graph 4

The biggest percentage of respondents at 38% reported verbal threats and insults from the “heterosexual” community. However, during the focus group discussions, it seemed to be emphasised by quite several participants that the LGBTIQ+ community was as big a threat to itself. The discussion captured an array of emotional concerns about LGBTIQ+ persons either putting their friends and organizations in harm’s way or actually carrying out threats against them, including blackmail. “A fellow LGBTIQ+ is causing me issues in Mbarara [a city in western Uganda]”, said a gay man from Mbarara, refusing to go into details. “Someone blackmailed a closeted person for 75,000,000 Uganda Shillings over a romance video [that they recorded of themselves being intimate]”, said another respondent. Another activist who works as a Reactor (documenting cases) said that in the period between 2019 and 2020, he had received between 20 to 30 cases of queer-on-queer blackmail.

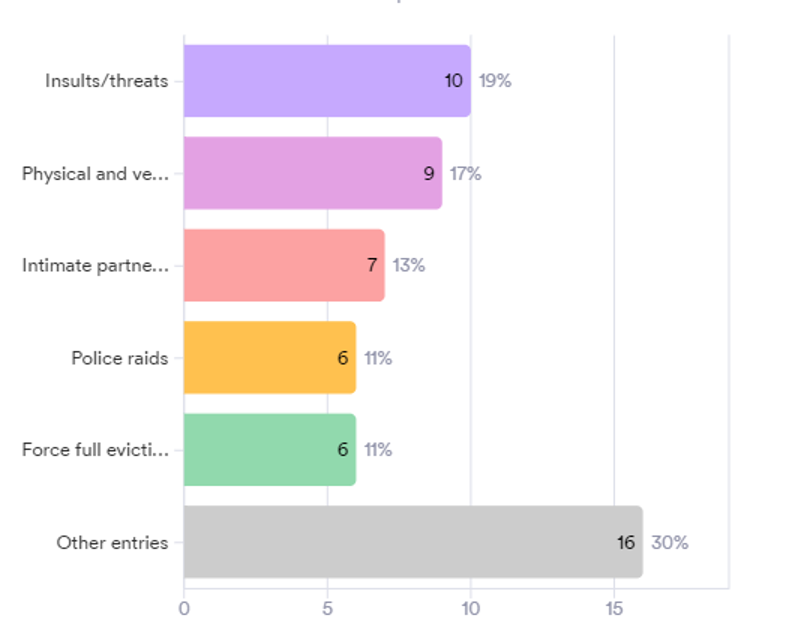

Intimate partner violence and harassment (IPV) was also highlighted in the discussions as an actual security concern. One activist reported that IPV was particularly commonly reported to his organization during the COVID 19 lockdown. In fact, in a survey question asking what the commonest insecurity incidence that happened during COVID 19 was, IPV came third among five other clear security incidents, outweighing police raids and forced evictions (see chart below). The further concern about IPV was exposing the LGBTIQ+ community to further threats from the general community. This is exemplified by an anecdote offered by a Transgender man who said:

“My ex-girlfriend became a security threat for me in 2019 where she went and reported me to the LC Chairperson that I was a transman who wants to recruit young girls at Sseguku Kampala into homosexuality. The Chairman came to arrest me and I had to flee the area.”

H._

Graph 5

*Insults and threats

*Physical attacks

*Intimate Partner Violence

*Police raids on offices

*Forceful eviction from homes

*Other entries

Note: The above graph is limited to violations during the COVID-19 period.

Another participant in the focus group discussions believed that the LGBTIQ+ community was spying on itself and reporting to the police. To support this, he reported that:

“Two weeks ago, I was arrested by Wembley [the name given to the national joint security team formed of the police, intelligence services and the army, officially known as the Violent Crimes Crack Unit or VCCU] at Kireka [the headquarters of Wembley]. The community [the LGBTIQ+] seems to be spying on us. The police showed me a police report on all LGBTIQ+ organizations plus some activists. There are spies in the LGBTIQ+ community!”

Names and initials withheld for respondent’s safety

In the past, it has sometimes been thought that the kind of information about LGBTIQ+ organizations that gets into the hands of the police was too detailed to be from an outsider and that some of the information would have only been known by the LGBTIQ+ members who frequent these organizations.

Police harassment, surveillance, arbitrary arrests and detention

Police harassment and arbitrary arrests and detention were reported by a total of 30% of the respondents. Diane Bakuraira, a staffer working with a programme called REAct at Sexual Minorities Uganda that documents security incidents against the LGBTIQ+ community with the aim of helping out the victims, reported that the commonest incidents they have so far received and documented in the system were to do with police harassment, threats and arrests. It was also reported that LGBTIQ+ organisations stationed near police posts were under constant scrutiny by the police officers in those stations. The reason given for this was that neighbours kept reporting the organisations to the local authorities including the police at these posts. Diane Bakuraira (referenced to prior), made a submission that during an organisational event in August 2020 at Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG), the police inquired about what was happening at the offices because according to the police, someone in the neighbourhood had called them to report that there were LGBTIQ+ people gathered at the offices so that they could probably effect an arrest or stop the event from happening. It was also expressed by respondents that the police engage in extortion in collaboration with some disgruntled members of the LGBTIQ+ community. According to one respondent, she reported a case to the police of having received a phone call from a person who identified themselves as a police officer demanding money or threatening to kill her (this phone number was identified via phone registries as truly belonging to a police officer according to the respondent).

However, respondents also raised the fact that once an LGBTIQ+ organisation has rented offices in an area, they needed to build rapport with the police in the area and the local leaders as a mitigation measure to bring about some measure of protection for the organisation.

“The police posts in Kigoowa (Kampala suburb) are not 100% a threat. Let us meet the police officers before because they are fed with false information. We will build some leeway with them. We can find someone neutral to connect us to the police”,

said SW, Executive Director at Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG), one of three LGBTIQ+ organizations based in the area referred to in the quote.

One other activist, however, mentioned that the reason why many police stations and posts are a threat to LGBTIQ+ individuals and organizations is that there are always new police officers posted to the stations and these have not yet been oriented on LGBTIQ+ rights, a pointer to the fact that some organizations and their human rights partners have carried out police training on LGBTIQ+ rights in the past.

Raids and destruction of property

18% of respondents reported raids on office premises and LGBTIQ+ shelters as an actual security incident, and 12% reported destruction of property instigated by homophobic malice and aforethought. The police raid on an LGBTIQ+ shelter in March 2020 attests to this.[17]

Transportation violence and threats

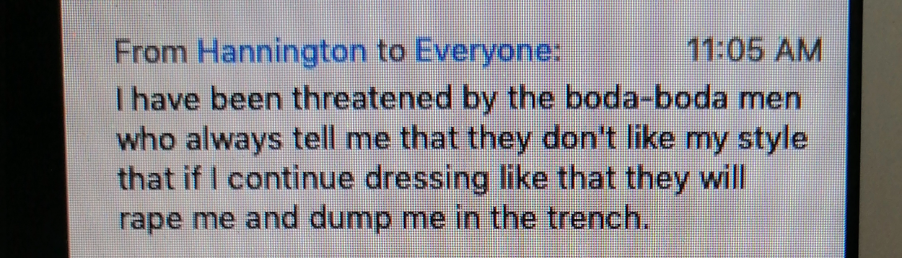

Transportation can be a problem for the LGBTIQ+ community because it exposes them to scrutiny. This is especially so for non-gender conforming persons and Transgender men and women. Uganda has a network of motorcycle transport systems called boda boda that mostly employs men as riders. These men can be toxic to LGBTIQ+ passengers. Hannington, a transman from Kampala gave a glimpse of the kind of threats that can come from this sector for people like him:

The specific effects of COVID 19 and the Presidential Guidelines on Prevention of COVID 19

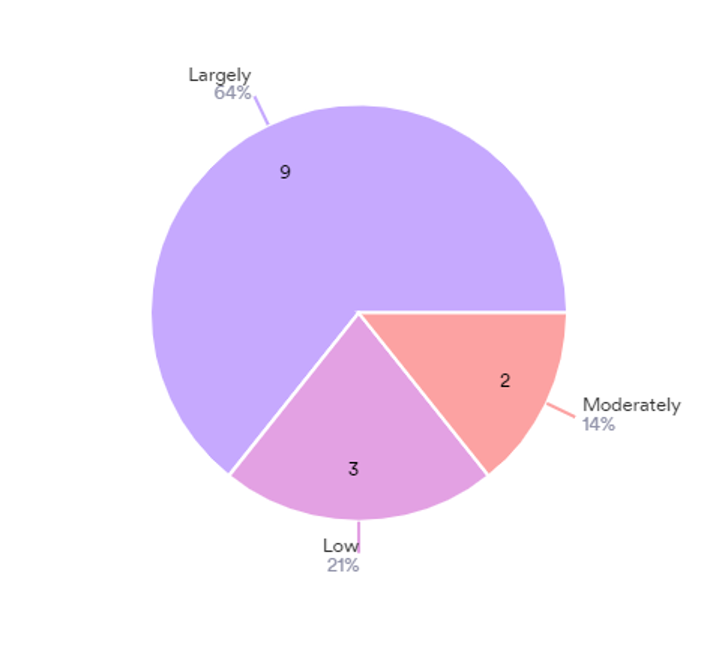

Piechart 1

The COVID 19 pandemic has had specific and uniquely differentiated effects on the lives of Ugandans. The LGBTIQ+ community and organizations did face their own challenges including in the security and safety of the area. When asked how much the pandemic affected their security and safety, 64% responded by saying it did to a larger extent. EG who works for Transgender Equality Uganda, particularly expressed how much the COVID 19 restrictions affected their transgender members. Many Transgender beneficiaries depended on sex work as the source of their income and during the restrictions, the police arrested a number of them as they did their work. It was also further revealed that because sex work was clamped down, some transgender persons started relying on their partners for sustenance, a situation that led to cases of IPV. The COVID 19 situation exacerbated the financial strains of the community so that it became difficult to sustain livelihoods. Consequently, according to Esther, there were a lot of evictions by landlords for non-payment of rent. Another consequence noted was that of mental health. Due to the pressures and stresses brought about by the economic hardships and isolation, the mental health of the transgender women community suffered. No reason was given for why it was particularly transgender women who suffered from inadequate mental health, except that the information was availed in that way because the organisation has more transgender women beneficiaries.

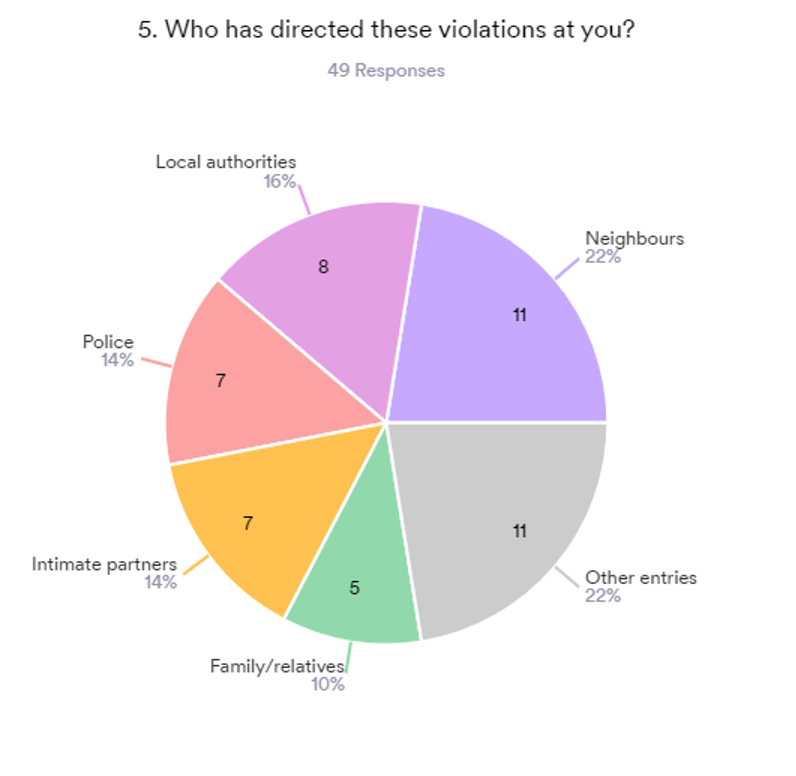

Perpetrators of security incidents and threats

Pie chart 2

Among the perpetrators of violations against the LGBTIQ+ community that came out in the survey, local community members, especially neighbours were identified as the most cause of insecurity for the community. 22% said neighbours were the main cause of violations against the community followed by local authorities (LCs or village council officials). Intimate partners and the police tied at 14%, suggesting that cases of IPV were a serious problem as police harassment, arbitrary arrests and detention, especially during the COVID 19 pandemic. the foregoing could be attributed to partners being locked up together at home, exposing them to more violence from their partners, or that the stress and anxiety caused by the lockdown generated feelings of anger and frustration culminating into either emotional or physical abuse and violence. Family and relatives scored at 10%, an indication that homophobia, harassment and violence based on sexual orientation or gender identity in family settings are high and a matter of concern. On average, in all sectors of society, both private and public, there is a more or less equal chance of there being contributors to violations and threats of violations against the LGBTIQ+ community or individuals.

Reporting security and safety cases and concerns to seek remedy

Despite the police and local councils being identified as one of the key perpetrators of insecurity for the LGBTIQ+ community, some individuals still reported that they have gone to the police and local councils to report violations against themselves. However, some reported rather going to other friendlier entities to report cases and to seek varied solutions or remedies. These entities included the National LGBTIQ+ Security Committee, paralegals who form part of legal aid projects for LGBTIQ+ persons in organisations like Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum (HRAPF) and, Defenders’ Protection Initiative (DPI), a protection organization. Other organizations that respondents reported going to seek solutions or remedies for cases of insecurity include SMUG, Uganda Network for Sex Work-led Organizations (UNESO) and, East African Sexual Health and Rights Initiative (UHAI-EASHRI). An example of a case where an organization sought remedy/solution for was the case of the arrest of Transgender Equality Uganda members in Busia, eastern Uganda in. However, those who went to the police to report security violations said that when they went, they concealed certain identifying details about the cases, therefore leaving out any incriminating details such as sexual orientation. The problem was however that the police rarely follow up the cases reported to them. They would provide the complainants with a reference number for the case but everything stops there. This however is positive so that when the accusation is made that the LGBTIQ+ community does not report violations against them to the police, there is evidence to show that they actually do, which is a good way to hold the police accountable. However, the challenge is whether these cases are reported as violations based on sexual orientation or gender identity and expression or as matters where no motive based on sexual orientation is raised.

Future influencing factors on security and safety

With the upcoming 2021 general elections, the safety and security of LGBTIQ+ persons could be compromised in more ways than one. It has become common place that electoral politics in Uganda are usually marred by violence and other human rights violations.[18] For the LGBTIQ+ community, this poses greater dangers such as from political hate speeches emanating from political aspirants for populist reasons to appease voters. In 2020, there have already been speeches made by political leaders that demonise the LGBTIQ+ community. Reference is made to speeches made by the President alluding to the opposition being supported by homosexuals from western countries.[19] This is worrying for the community.

The insecurity arising from the elections is however not only limited to issues of violence during the electoral period. When the elections will be over, there’s are likely to be changes in parliament with new legislators coming in. Some of the newly elected leaders could pose a threat to the LGBTIQ+ community as they may not be well versed with the LGBTIQ+ rights much less believe in them. This could be a setback to the already achieved progress with some of the stakeholders whose support and backup is very vital in ensuring safety.

The continuation of COVID-19 also remains an influencing factor owing to the uncertainty regarding when COVID 19 containment measures and other restrictions will be lifted. This is even with the emergence of discussions around discoveries and approval of COVID 19 vaccines in certain developed countries. It is not yet clear how fast the vaccine will be made available or affordable to populations in Africa, especially Uganda. As earlier stated, the COVID-19 pandemic is said to have largely affected the security of the members of the LGBTIQ+ communities, refer to pie chart 1. The uncertainty of this period means that the security issues that came along with it are likely to continue as long as the situation is still the same. This is despite the acknowledgment that situation has been improved with the ease of the lock down measures. However, some of the issues remain the same.

CHAPTER THREE

SOLUTIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND MITIGATING MEASURES

The need for more security and safety capacity building and re-tooling

As early as the late 2000s when the attempt to start legislating on the Anti-homosexuality Bill of 2009 begun, organizations like Sexual Minorities Uganda and Freedom and Roam Uganda had started to be trained on security and safety by expert organizations such as Defend Defenders and Protection International using common manuals.[20] According to the survey, these trainings have continued with the same security training organizations as well as additional protection/security training organizations. Respondents said they had received additional security training and tools from organizations such as HER Internet[21], SMUG, Defenders’ Protection Initiative and Frontline Defenders. Most respondents, when asked if they had security and safety protocols, plans, policies or tools in place for their organizations or if they had been trained on security and safety, responded in the affirmative. A few organizations reported having cameras installed at their organizational premises. The question was whether these were actively used to mitigate incidents of insecurity. However, some respondents said they had never been trained or had received training too long ago for them to remember. Respondents therefore expressed the need to conduct more trainings and refreshers on security and safety, including digital security. This especially considering that the movement keeps having fresh activists joining or getting employed in organizations who have never received the trainings.

The need to upscale mental health programmes

Respondents expressed the need for mental wellbeing programmes as a way of taking care of the mental safety of the community as well as activists. There are programmes on mental health that are run by organisations like SMUG and Ice Breakers that could be upscaled to reach more people. The COVID 19 pandemic has increased this need with the direct correlation with loss of sources of income, especially due to the fact some of the restrictive conditions still exist for sex worker LGBTIQ+ persons and those working in the entertainment and leisure industry.

The need to do more capacity building for the police and local council leaders

Stemming from the observation that the police and local council leaders can be a security hindrance for LGBTIQ+ persons rather than enhancers of safety and security for the community, there is need to upscale capacity building for them on sexual orientation, SOGIE and rights. This will help them develop empathy and understanding for the community and avoid society influencing their actions through accusations that lead to them harassing members of the LGBTIQ+ community. Relatedly, organizations need to start making efforts towards working more with authorities in their areas of jurisdiction to create rapport between them and the police and local leaders, something that has already been exemplified as possible by some few organisations.

The need for legal reform

Although there are processes by a few allied organisations such as HRAPF towards dialoguing for legal reform of penal code provisions that criminalise same-sex acts, vagrancy and other provisions that impact on the LGBTIQ+ lives and bodies, there is now need for a more expedited process to lead to the total removal of these laws. Certain countries in Africa such as Botswana, Seychelles, Cape Verde and Angola have already set this pace. Others such as Kenya and the Kingdom of Eswatini have also sought court redress on such laws. It is high time Ugandan activists, organisations and other likeminded stakeholders lobby for the decriminalisation of consensual same-sex sexual acts, including by instituting a constitutional petition. Advocacy and dialogue with legal entities like the Uganda Law Reform Commission and the legislature need to be up scaled in order to lead to decriminalisation of same-sex sexual conduct because these laws inform the homophobia that is within the society and within public institutions.

The need for changing the narrative through education and awareness creation

There is need to change the negative narratives around LGBTIQ+ identities. How this is to be done is a matter for debate. Societal norms, believes and value systems take years, even decades to change. However, innovative ways need to be summoned in order to change attitudes in society that are hostile and unfriendly to LGBTIQ persons.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this research are minimal to a more or less rapid situational assessment of the situation of security and safety for the LGBTIQ+ community of individuals and activists as well the organisations that do the programming for LGBTIQ+ community needs. In as much as efforts have been made to capture as many aspects of the situation of security and safety as possible, there will be the need to conduct a more detailed analysis of the situation in the near future. Other research projects related to this can capture these aspects. It would be useful to conduct a more detailed analysis of mental health as a factor of security and safety as well as the impact of elective politics and its processes on the safety and security or LGBTIQ+ persons.

References

[1] Mbarara Rise Foundation, Restore safety and security for LGBTQ in Uganda, GlobalGiving, https://www.globalgiving.org/projects/restore-safety-and-security-for-lgbtq-in-uganda/reports/ (accessed 15 December, 2020)

[2] Same as above

[3] Human Rights Watch, Uganda: Stop police harassment of LGBT people, drop charges against dozens detained in recent police roundups, November 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/17/uganda-stop-police-harassment-lgbt-people (accessed 28th September 2020)

[4] World Health Organisation, WHO-Director General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID 19, 11 March 2020, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 (accessed 28 September, 2020)

[5] Neela Ghoshal, Uganda LGBT shelter residents arrested on COVID-19 pretext: Release 20 detainees, end arbitrary arrests, Human Rights Watch, April 3, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/03/uganda-lgbt-shelter-residents-arrested-covid-19-pretext (accessed 15 December 2020)

[6] Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG), The impact of COVID-19 on the LGBTIQ community in Uganda, August 2020, https://sexualminoritiesuganda.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Report-on-the-impact-of-COVID19-on-the-LGBTIQ-community-in-Uganda.pdf (accessed 15 December 2020)

[7] https://faruganda.org/ (accessed 15 December 2020)

[8] Uganda Legal Information Institute (ULII), Anti Homosexuality Act 2014 2013, https://ulii.org/ug/legislation/act/2015/2014 (accessed 15 December 2020)

[9] Abby Ohlheiser, Uganda’s new Anti-homosexuality law was inspired by American activists, The Atlantic, December 20, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/12/uganda-passes-law-punishes-homosexuality-life-imprisonment/356365/ (accessed 15 December 2020)

[10] Uganda Media Centre, Ministry of ICT and National Guidance, Republic of Uganda, President Museveni COVID-19 guidelines to the nation on Corona Virus, Wednesday March 18, 2020, https://www.mediacentre.go.ug/media/president-museveni-covidc19-guidelines-nation-corona-virus (accessed 15 December 2020)

[11] Same as above

[12] See 6 above

[13] Several safety and protection organisations have contributed to training and tooling LGBTIQ+ persons and activists on security and safety. Some organisations have contributed to providing non-legal as well as legal remedies to victims of insecurity.

[14] https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/people/gender-fluid-what-mean-definition-non-binary-difference-222158 (accessed 15 December 2020)

[15] Penal Code Act Cap 120 of Uganda, Sections 145(a), 145 (c ), 146 & 147

[16] Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, Section 31, 2(a)

[17] Rodney Muhumuza, LGBT community raided in Uganda over social distancing, 1 April 2020, abc News, https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/lgbt-community-raided-uganda-social-distancing-69915445 (accessed 4 November 2020)

[18] Andrew Mwenda, On Uganda’s elections violence, The Independent, November 19, 2020, https://www.independent.co.ug/on-ugandas-election-violence/ (accessed 20 December 2020)

[19] Crispus Mugisha, Museveni attacks homosexuals, foreign groups, says they are sponsoring opposition protests, Nile Post, 20 November 2020, https://nilepost.co.ug/2020/11/20/museveni-attacks-homosexuals-foreign-groups-says-they-are-sponsoring-opposition-protests/, (accessed 15 December 2020)

[20] New protection manual for human rights defenders, Protection International, 2009, Brussels, Belgium

[21] https://www.facebook.com/herinternet/ (accessed 4 November 2020)